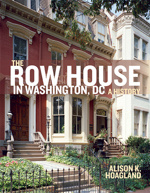

Today, we are happy to bring you our conversation with Alison K. Hoagland, author of The Row House in Washington, DC: A History.

What inspired you to write this book?

Washington, DC, is a row-house city! Despite the usual association of the District with its monuments, there are far more row houses than another other building type in this city. Row houses frame the streets, characterize the neighborhoods, and over time have sheltered a wide variety of people, from laborers and laundresses living in alley dwellings to lawyers and ambassadors residing in posh residences. Mostly, though, a broad middle class has inhabited this building type, raising families and working in the neighborhood. Row houses have experienced racial change and racial segregation; they have gone in and out of fashion; they have been equipped, or not, with comforts and conveniences. Row houses tell the history of the people of this city.

What did you learn and what are you hoping readers will learn from your book?

Row houses are products of many constraints. Their abutting neighbors mean that light and air can be obtained only from the front and back of the house, severely limiting the plan. Building regulations, which changed as science and fashion changed, guided the houses’ materials, bay windows, rear ells, and so forth. But despite these constraints, row houses are flexible in the way that they are used. Although they look like single-family dwellings, they have accommodated many housing situations as homeowners have taken in boarders and lodgers or created separate apartments. They continue to serve a variety of residents with different needs and they have proven to be a very resilient form of housing.

What surprised you the most in the process of writing your book?

I was not prepared for the frequency with which kitchens were located in basements, but it was a common solution in the nineteenth century. It seems to assume that there is at least one servant, and maybe additionally a cook, but it still amazes me that anyone would want their meals prepared in the darkest and dankest part of the house. Upscale row houses were equipped with dumbwaiters and dining was clearly intended to happen on the upper floor, but in many others the front room of the basement served as the dining room, with the kitchen in the rear.

What’s your favorite anecdote from your book?

The story of Josephine Patterson stays with me. She was an African American who worked as a kindergarten teacher in the public schools for forty-nine years. She bought a row house for her parents and siblings on the edge of Capitol Hill, then in 1929 she bought another near Dupont Circle. This house had three stories on a raised basement, with a two-story bay window topped by an open porch, and was nearly four times the space of the previous house. She and her extended family lived there for more than thirty years. She married when she was in her sixties and moved to a semidetached house in Manor Park, then a freestanding one in Brightwood. She clearly used her real estate to leverage more desirable houses, navigating the segregated landscape.

What’s next?

I’m considering a project about a seaport village in Connecticut that was remade in a Colonial Revival image in the early twentieth century, just as Portuguese millworkers were beginning to characterize the population. The romance of whaling captains’ houses and a village green (where the railroad hotel had been standing) contrasts with the dirt and noise of mills and machine shops. I think there’s a story there.