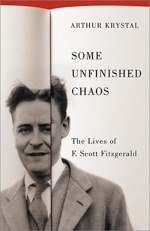

One Hundred Years of The Great Gatsby: An Excerpt from Some Unfinished Chaos: The Lives of F. Scott Fitzgerald by Arthur Krystal

One Hundred Years of The Great Gatsby: An Excerpt from Some Unfinished Chaos: The Lives of F. Scott Fitzgerald by Arthur Krystal

F. Scott Fitzgerald would be the first to point out the delicious irony of his posthumous fame. Although he published four novels and four collections of short stories (his fifth novel was never finished), it’s not the work alone that accounts for his lasting reputation. In hindsight there is something almost archetypal about Fitzgerald’s life, though at the time it would have been difficult to predict the dappled glory that one day would day become associated with his name. Somehow the unique combination of the personal and the public—the coming of age of a Scots-Irish writer from the Midwest and the coming of age of America itself—made the name of Fitzgerald a permanent part of our cultural lexicon.

Wherever you look, he jumps out at us. A movie is getting made, a house he rented is being sold, an opera or a play based on The Great Gatsby is being performed. An abbreviated list of my own sightings includes: Holden Caulfield’s homage to Gatsby in The Catcher in the Rye (“I was crazy about The Great Gatsby. Old Gatsby. Old sport. That killed me”); Bob Dylan’s Ballad of a Thin Man (“You’ve been through all of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s books”); Richard Yates’s short story “Goodbye to Sally” (about a disgruntled screenwriter haunted by Fitzgerald’s Hollywood career); Andy Kaufman reading The Great Gatsby aloud on Saturday Night Live; John Harbison’s opera of the same name; Martin Scorsese’s fictional production of Gatsby on the HBO series Entourage; an episode of South Park, in which the snarky little characters are forced to read Gatsby to determine if they have Attention Deficit Disorder; Azar Nafisi’s trial of Gatsby in Reading Lolita in Tehran; a rather stiff rendition of Fitzgerald in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris; Taylor Swift’s “This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things” includes the line “Feeling so Gatsby for that whole year;” and, of all things, a video game based on Gatsby (“Experience the Roaring Twenties first-hand as you uncover secrets behind the richly decadent façade. Explore one of the most tragic tales in literary history”).

There is also something known in economic circles as “The Great Gatsby Curve,” illustrating “the connection between concentration of wealth in one generation and the ability of those in the next generation to move up the economic ladder compared to their parents.” Gatsby is no longer just a story; it’s an industry. Novel after novel features “Gatsby” in the title: Gatsby’s Girl, Gatsby’s Last Resort; Gatsby’s Vineyard; The Summer We Read Gatsby, while others—Erich Rauchway’s Banana Republican and Tom Carson’s Daisy Buchanan’s Daughter—simply lean on the original. As for the original itself, around 30 million copies have been sold worldwide and until 2021, when its copyright expires, more than 500,000 copies were sold annually in the United States alone.

And then, with apparently no end in sight, the films: those based on the fiction and those dealing with aspects of Fitzgerald’s life. In 2012 the 125 million-dollar production of The Great Gatsby in 3-D opened to much fanfare, and more recently a tepidly received TV series about Zelda with an inane title (Z: The Beginning of Everything), ran on Amazon. Just one more sighting: from 2005 to 2012 the Elevator Repair Service theater troupe toured America and Europe with a six-and-a-half hour word-for-word enactment of Gatsby (called Gatz), which, according to the New York Times theater critic, “captured—in inventively theatrical terms—the unmatchable, heady rush of falling in love with a book.”

Historically, though, it was not love at first sight. The novel sold only around twenty-two thousand copies in 1925, and though it received high marks from most critics, it wasn’t until the 1950s that Gatsby actually became great. Indeed, it is now considered such a remarkable achievement that without it, Fitzgerald might be nothing more than a singular but somewhat minor writer, whose fall from grace in the 1930s would probably not have acquired the mythic overtones it has today. This view is not as blasphemous as might first seem. Gore Vidal, for one, argued that it was Fitzgerald’s sad life rather than his work that “continues to provide not only English Departments but the movies with a Cautionary Tale of the first magnitude.” But even Vidal would concede that with Gatsby, Fitzgerald’s stature as both novelist and iconic American writer became unassailable. And since Gatsby figures, in the minds of many readers, as the Great American Novel, it follows that Fitzgerald himself must embody something distinctly American.

Now the pleasantly fuzzy notion of the Great American Novel does not actually require corroboration; like many things about America it exists more in the imagination than in fact. Still the idea of such a work remains, and for many commentators it is embodies in a book of fewer than fifty thousand words, whose action is confined pretty much to Long Island and parts of Manhattan in the year 1922. One year, a specific locale, fifty thousand words. Strictly speaking, however, no consensus about The Great Gatsby’s “Americanness” exists. Trilling believed that the Gatsby himself inevitably came to stand for America, but this does not necessarily stamp the book with the national seal.

Other critics, however, are not bothered by such niceties. Apparently, The Great Gatsby is “the major statement of America realized as world power and imperial presence, as ideologically crucial in its day as Franklin’s Autobiography had been in its.” A ringing endorsement not shared by the critic who wondered if Gatsby does not embody “a criticism of American experience—not of manners, but of a basic historic attitude to life—more radical than anything in [Henry] James’s own assessment of the deficiencies of his country. The theme of Gatsby is the withering of the American dream.”

The problem may lie in the implicit conflation of America and the American Dream. They’re not the same, except on parchment. Nearly a quarter of a century ago, Thomas Flanagan scoffed at the notion that Gatsby is about something called the American Dream: “If you whispered into a reader’s sleeping ear the words ‘Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby,’ she would murmur drowsily ‘and the corruption of the American dream.’” There probably is an American dream, Flanagan conceded, “and it probably deserves some of the things that are said about it. But this is not the subject of Fitzgerald’s wonderful novel, which is ‘about’ our entrance into the world ‘trailing clouds of glory’ until ‘At length the Man perceives it die away, And fade into the light of common day.’”

Well, that might need some pondering. Wordsworth’s imprimatur incidentally did not come to Flanagan unbidden. The lines appear in the third and last of the pieces that constitute The Crack-Up and do not refer to Gatsby but to Fitzgerald’s emotional distance from the subjects he writes about. No, it was not the American Dream that Fitzgerald wanted to set down—but what does that matter? There is by now no disputing that he added to the dream both in his own person and in that of Jay Gatsby.

Aside from Scott’s spectacular rise and fall, which set the tone for subsequent American writers who exploded out of the gate but faded toward the end of their careers, there is something quintessentially American about his life. Indeed, one might say that for reasons of heritage, timing, circumstance, and temperament, he, more than any other writer, stood the best chance of producing a novel that would reflect not just the American Dream but also the ineluctable American identity that was then taking shape.

Fitzgerald came along at a moment when the country was entering upon a period of unprecedented social, technological, and artistic growth, when advances in marketing and media were instrumental in disseminating the idea (whether real or not) of a bountiful, unified, and culturally cohesive nation. Until 1925, the times were not ripe for the Great American Novel—how could such a book exist unless the country itself was great?—and then suddenly after 1918 it seemed to be.

QuickLinks

Find a BookFor Our AuthorsRights and PermissionsRotunda Digital ImprintSupport UVA PressCareer OpportunitiesWalker Cowen Memorial PrizePrivacy PolicyContact Us

- P.O. Box 400318 (Postal)

- Charlottesville, VA 22904-4318

- 210 Sprigg Lane (Courier)

- Charlottesville, VA 22903-2417

- 434 924-3468 (main)

- 1-800-831-3406 (toll-free)

- 434 982-2655 (fax)

the future

of publishing

Affiliates