Q&A with Winner of the New Academy Prize in Literature, Maryse Condé, and translator Nicole Simek

Q&A with Winner of the New Academy Prize in Literature, Maryse Condé, and translator Nicole Simek

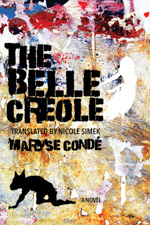

As The New York Times Book Review writes of Maryse Condé in their review of her newly translated book The Belle Créole, "For the past half century, Condé has been chronicling the black diaspora in novels that are rollicking and scandalous, that examine gender and culture, class and religion, African and Caribbean society. She performs a kind of alchemic conversion from abstract theories of power to very human lusts and appetites, where costs are paid in the flesh.

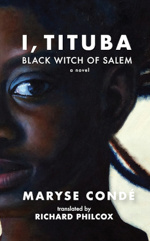

"One of the hallmarks of her genius is to approach her themes from unexpected subject positions, like the enslaved woman who faces a witchcraft trial in 'I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem.' Condé’s multigenerational family saga 'Segu,' like 'Anna Karenina' or 'One Hundred Years of Solitude,' is a metonym for a time and a people — in this case a declining empire in Mali amid the rise of Islam and the trans-Atlantic slave trade. . . .

"In 2018, Condé was awarded the first and only New Academy Prize in Literature, nicknamed the 'Alternative Nobel.' It was the year that sexual assault and corruption led to a crisis of validity for the Swedish Academy, and the awarding of the world’s most prestigious literary honor was postponed. A group of librarians established the New Academy Prize as a one-time stopgap, and Condé was voted the winner from a small group of illustrious finalists. . . .

"The Belle Créole, first published in 2001, is set in Guadeloupe, where all is not well. In the decade after the devastation of Hurricane Hugo, neocolonial mismanagement, labor strikes and staggering youth unemployment have shaken the foundations of society. The book opens in a packed courtroom, the moment after a jury has acquitted Dieudonné Sabrina, our protagonist, of the murder of his lover.

"Everyone present, including the jury, knows he has indeed killed the woman. But Loraine, his lover, was a middle-aged bekée — a wealthy white Creole descendant of colonial plantation owners. (The use of Antillean Creole versus 'French-French' is highly politicized on the island, a point made clear in this skillful translation.) Dieudonné’s lawyer, rather than deny the facts, has built his defense on manipulating the frustrations of the island’s black majority. He has 'put the whole of society on trial, invoking colonial domination and its trail of evils.'”

We invited Condé to do a q&a with her translator for The Belle Créole, Nicole Simek, and we're pleased to offer their conversation below. You can also read a q&a with Simek in which she discusses the process of translating this powerful book in the Los Angeles Review of Books, and reviews of the book in Asymptote and The Book Slut.

Q. You have written works in all sorts of genres—novels, plays, literary criticism, science fiction for children, memoirs… What has writing meant to you, in your life? Have these various modes of writing meant something different to you at different moments in time?

A: To ask a writer what writing means to her is somewhat strange. For a writer, writing means everything: life, death, love, illness, expectations and disappointments, just to name a few. Since writing means everything to me this explains why I tried throughout my career so many genres as I was looking for the one most suitable for me. I believe the novel for adults suits me fine because of its diversity and complexity.

Q. What led you to write The Belle Créole? What questions did you want to explore in this novel?

A: Guadeloupe is an island populated by very different ethnic groups: the Békés or white Creoles, the descendants of African slaves and the Indians. Your origin defines your place in society. I explored in The Belle Creole how difficult it is for a descendant of the African slaves to find his place in a society governed by the color of skin and money and escape the stereotype imposed on him. Dieudonné, the hero of The Belle Creole, is a born loser because of the color of his skin and cannot succeed in such a society. If you allow me, I would like to add a detail, The Belle Creole as a title is a joke. It traditionally refers to the vocabulary used to depict a Caribbean beauty. In the novel it is the opposite of this exotic term.

Q. Another important question The Belle Créole raises is how we should judge a person’s public and private acts, when the two are in conflict. You discuss similar questions elsewhere, in What is Africa To Me? Fragments of a True-to-Life Autobiography, for example, or in The Wondrous and Tragic Life of Ivan and Ivana. What role do you see literature playing in shaping ethical judgments?

A: I belong to a society which does not value written literature. An oral storyteller is better equipped to move the minds of the people, express the contradictions of the community and tell of disappointments and bring about revolt.

Q. The society of The Belle Créole is one that appears to be disintegrating, in ways that might remind readers today of the destruction wreaked by the COVID-19 pandemic, although the causes for this dysfunction are very different. Is the likeness completely coincidental, or does the current crisis point to problems in social, political, or economic structures that are similar in some respects to the ones you explore in the novel?

A: I am not Bill Gates and did not think of the virus at that time. But you are free to compare the effects of slavery and colonialism with the impact of a powerful virus. Slavery and colonialism were the negation of religion, language and home.

QuickLinks

Find a BookFor Our AuthorsRights and PermissionsRotunda Digital ImprintSupport UVA PressCareer OpportunitiesWalker Cowen Memorial PrizePrivacy PolicyContact Us

- P.O. Box 400318 (Postal)

- Charlottesville, VA 22904-4318

- 210 Sprigg Lane (Courier)

- Charlottesville, VA 22903-2417

- 434 924-3468 (main)

- 1-800-831-3406 (toll-free)

- 434 982-2655 (fax)

the future

of publishing

Affiliates