Honoring Dr. King: Creating the Path to Non-Violence

Honoring Dr. King: Creating the Path to Non-Violence

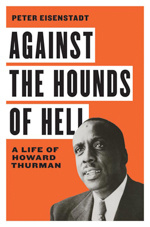

We join everyone celebrating MLK Day with this blog post from Peter Eisenstadt, author of the new book Against the Hounds of Hell: A Life of Howard Thurman (February 2021).

Honoring Dr. King: Creating the Path to Non-Violence

Every four years, the anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday is celebrated about two weeks after a joint session of Congress certifies the results of the recent presidential election. Until this year, the closeness of the two events has been unremarkable and unremarked upon. This year, of course, is different. On January 6, a violent mob breached several layers of security at the Capitol and killed and wounded police officers amid destructive mayhem. Today, the country braces for more unrest, as we celebrate the life and legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr. What would King have had to say to the mob as it mounted the Capitol steps? What is the purpose or efficacy of radical nonviolence as a counter to an armed, murderous insurrection?

On Martin Luther King Day many words are spoken about nonviolence, but the word and concept are rarely interrogated or simply relegated to the large class of “beautiful but impractical” ideas. King would have been appalled by the insurrectionary violence at the Capitol, but not surprised. White violence and the asymmetries of power shaped the contours of every Black life in the America into which he was born, came of age, and was murdered. He never underestimated the strength of the resistance to the Black freedom struggle. And yet he was undaunted in his belief in nonviolence.

For King, nonviolence was less a political tactic, to be switched on and off, and more of a lifelong spiritual discipline. In this, he learned much from his older contemporary, the African American religious thinker Howard Thurman (1899–1981), the first prominent Black pacifist. Like King, Thurman was a scion of Jim Crow South, and like King, he was a Morehouse College graduate. It was at Morehouse that Thurman was converted to pacifism in the early 1920s. His pacifism was specific to his circumstances. He found in it “a place to stand in my own spirit—a place so profoundly affirming that I was strengthened by a sense of immunity to the assaults of the white world of Atlanta, Georgia.” At the time, pacifism was changing from a movement of well-to-do well-intentioned people who wished to do away with war to a commitment to a way of living. For Thurman the primary focus of his pacifism was to counter white violence, explicit and implicit. By affirming himself, he denied dominion to the forces that would contort and diminish Black lives. His philosophy of nonviolence boiled down to these tenets: Do not give into fear, do not be afraid to speak truth, or hide behind comfortable lies. Do not allow hate to dominate your thoughts or actions. And then begin the process, painful on both sides, of deep reconciliation with one’s former oppressors. Thurman outlined his thoughts about radical nonviolence in his most important book, Jesus and the Disinherited, in 1949. Martin Luther King, Jr., then a second year seminary student, was one of its first readers. It became one of his favorite books; he often carried it on his travels.

Thurman crossed paths with King occasionally. In 1953–54, during Thurman’s first year as dean of chapel at Boston University, for example, the younger King was in residence, completing his dissertation, often attending chapel services to hear Thurman preach. They would stay in touch as King made his ascent from family friend and graduate student to one of the most famous people in the world. Thurman’s influence on other leaders of the civil rights movement was even more direct; he directly mentored both James Farmer, his student at Howard University, and a co-founder of CORE in 1942, the first civil rights organization to systematically practice radical nonviolence, and Pauli Murray, another student he met at Howard.

Thurman closely followed King’s career and the trajectory of the civil rights movement. After hearing of King’s murder on April 4, 1968, Thurman was distraught. It was an assassination of a friend, and an assassination of everything he held dear about his country and the struggle of Black Americans for their freedom. Still, he accepted his public role as a speaker, explainer, and comforter. He told one audience that the point of nonviolence was not to refrain from violence, but to challenge it, forcefully, creatively, and collectively: “If Martin had been an apostle of nonviolence without adding nonviolent direct action, then at the center of his nonviolence would have been a sort of sticky piety.” At the same time, Thurman explained that the purpose of nonviolent direct action is less to defeat one’s opponents but to convert them and make them see the hopelessness and the evil of their former positions: “Martin was sure that there is a place in every man’s heart that waits and listens to the sound of the genuine in every other man. And we must therefore, reduce all of the other noises created by fear, by poverty, by panic, by hate, that the sound of the genuine in your heart might be heard by the sound of the genuine in my heart.”

King titled his last book Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? It is always a pertinent question. There have been, in the last few days, calls for “healing” and “reconciliation” by the aiders and abetters of violence. Thurman and King had no patience with sham or faux reconciliations, weak compromises that left everyone dissatisfied, or efforts to “understand” one’s opponents that accepted their biases and prejudices at face value. Radical nonviolence, for Thurman and for King, was a spiritual discipline to transform oneself, one’s opponents, and society as a whole. Either our efforts to transform the world for the better must be rooted in the recognition of our common humanity, or they are doomed to failure. As Thurman told the crowd at Fellowship Church, the interracial church in San Francisco that he had founded, on the Sunday after King’s death: “For better or worse we are tied together in one bundle and I can never be what I must be until you are what you must be; for better or worse that is the only option. And to reject it is to reject life. And to reject life is not only to deny the validity of the life of Martin Luther King, Jr. but it is to make God repent that he ever gave us a chance to live. And let us not do that.”

Today and everyday let us all work to create a world where Dr. King’s vision of nonviolence may be difficult to achieve but far from impossible.

Read more about Against the Hounds of Hell here.

QuickLinks

Find a BookFor Our AuthorsRights and PermissionsRotunda Digital ImprintSupport UVA PressCareer OpportunitiesWalker Cowen Memorial PrizePrivacy PolicyContact Us

- P.O. Box 400318 (Postal)

- Charlottesville, VA 22904-4318

- 210 Sprigg Lane (Courier)

- Charlottesville, VA 22903-2417

- 434 924-3468 (main)

- 1-800-831-3406 (toll-free)

- 434 982-2655 (fax)

the future

of publishing

Affiliates